Thousands of people have since died, towns and cities such as Mariupol lie in ruins and 13 million people have been displaced. But the questions remain: what was it all for and how will it end?

What was Putin's original goal?

The Russian leader's initial aim was to overrun Ukraine and depose its government, ending for good its desire to join the Western defensive alliance Nato. After a month of failures, he abandoned his bid to capture the capital Kyiv and turned his ambitions to Ukraine's east and south.

Launching the invasion on 24 February he told the Russian people his goal was to "demilitarise and de-Nazify Ukraine". His declared aim was to protect people subjected to what he called eight years of bullying and genocide by Ukraine's government. Another objective was soon added: ensuring Ukraine's neutral status .

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov spoke of freeing Ukraine from oppression while foreign intelligence chief Sergei Naryshkin argued "Russia's future and its future place in the world are at stake".

Ukraine's democratically elected president, Volodymyr Zelensky, said "the enemy has designated me as target number one; my family is target number two". His adviser said Russian troops made two attempts to storm the presidential compound.

Russia's leader refused to call it an invasion or a war. Moscow continues to coin Europe's biggest war since 1945 a "special military operation".

The claims of Nazis and genocide in Ukraine are completely unfounded but part of a narrative repeated by Russia for years. "It's crazy, sometimes not even they can explain what they are referring to," complained Ukraine's foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba.

However, an opinion piece by state-run news agency Ria Novosti made clear that "denazification is inevitably also de-Ukrainisation" - in effect erasing the modern state.

And it is Russia that is now accused by the international community of carrying out war crimes. Several countries including the US and Canada go further and call it genocide.

After so much destruction, the Russian leader's words ring very hollow now: "It is not our plan to occupy the Ukrainian territory; we do not intend to impose anything on anyone by force."

How have Putin's aims changed?

A month into the invasion, Russia pulled back from Kyiv and declared its main goal was the "liberation of Donbas" - broadly referring to Ukraine's eastern regions of Luhansk and Donetsk. More than a third of this area was already seized by Russian proxy forces in a war that began in 2014, now Russia wanted to conquer all of it.

The Kremlin claimed it had "generally accomplished" the aims of the invasion's first phase, which it defined as considerably reducing Ukraine's combat potential. But it became clear from Russia's withdrawal that it had scaled back its ambitions.

"Putin needs a victory," said Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council. "At least he needs something he can present to his constituency at home as a victory."

Russian officials are now focused on seizing the two big eastern regions and creating a land corridor along the south coast, east from Crimea to the Russian border. They have claimed control of the southern region of Kherson and a leading Russian general has said they have hopes of seizing territory further west along the Black Sea coast towards Odesa and beyond.

"Control over the south of Ukraine is another way out to Transnistria," said Maj Gen Rustam Minnekayev, referring to a breakaway area of Moldova, where Russia has some 1,500 troops.

If Russia does capture both eastern regions, it will most likely try to annexe them after a sham vote, as it did with Crimea in 2014. Ukraine also accuses occupying forces in Kherson of planning a referendum on creating separatist entity: they are already introducing Russia's currency, the rouble, from 1 May.

Capturing Donbas and the land corridor is a mandatory minimum for the Kremlin, warns Tatiana Stanovaya, of analysis firm RPolitik and the Carnegie Moscow Center: "They will keep going. I always hear the same phrase - 'we have no choice but to escalate'."

The powerful head of Russia's security council, Nikolai Patrushev, has spoken of Ukraine disintegrating into "several states", blaming Ukrainian and Western hatred of Russia.

The question is whether Russian forces have the numbers to press forward. By not declaring this a war, the Kremlin cannot mobilise nationally and military analyst Michael Kofman believes unless that happens Russia's Donbas offensive is the last it can attempt.

Is there a way out?

There is little sign of any negotiated end to this war in the immediate future.

A few weeks into the war, Russia said it was considering a Ukrainian proposal of neutrality, but there have been no negotiations since the end of March.

President Putin told the UN Secretary General at the end of April "we are negotiating, we do not reject [talks]", but he earlier declared negotiations at a dead end. After a meeting with the Russian leader, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer gave a very downbeat assessment of a man who had entered into a "logic of war".

Ukraine's Volodymyr Zelensky had already accepted that Ukraine would not join Nato: "It's a truth and it must be recognised." But after apparent Russian atrocities came to light in Bucha, Mariupol and elsewhere, he made it clear there would be no more talks until Russia withdrew from all territories seized since 24 February.

In its offer of neutrality proposed at the end of March, Kyiv said:

- Ukraine would become a non-aligned and "non-nuclear" state, with no foreign military bases or contingents on its territory

- Strict, legally binding guarantees would require other countries to protect a neutral Ukraine in the event of attack

- Within three days guarantor states would have to hold consultations and come to Ukraine's defence

- Ukraine would be allowed to join the European Union, but would not enter military-political alliances and any international exercises would require consent of guarantor states

- The future status of Russian-annexed Crimea would be negotiated over the next 15 years

But neutrality for Vladimir Putin was never likely to be enough.

"Ultimately [Putin] wanted to divide the country and I think it's becoming more evident that's what he wants," says Barbara Zanchetta of King's College London's Department of War Studies.

While the Kremlin wants to annex some areas of Ukraine, Tatiana Stanovaya believes "much more important is the fate of Ukraine: Putin wants to end Ukraine as a current state".

How Putin sees Ukraine

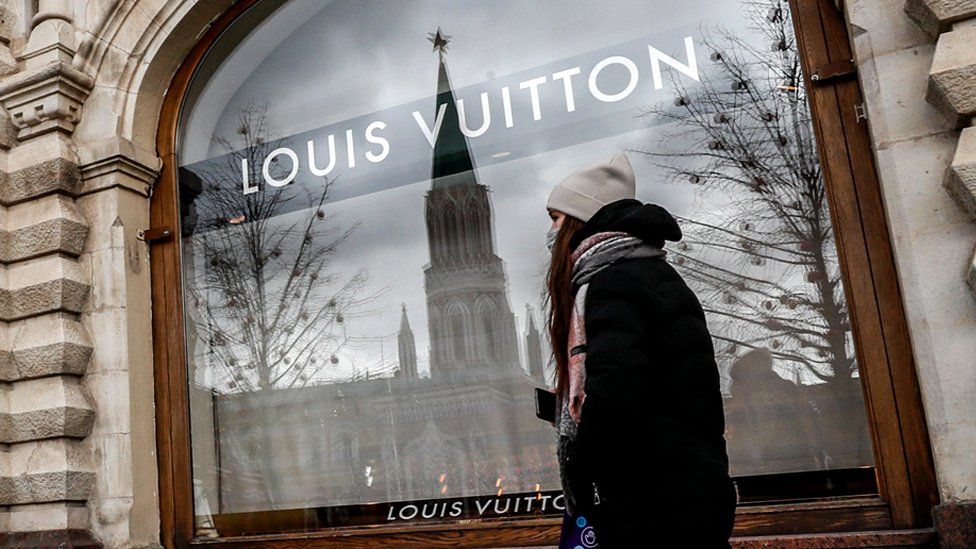

Since Ukraine achieved independence in 1991, as the Soviet Union collapsed, it has gradually looked to the West - both the EU and Nato.

Russia's leader has sought to reverse that, seeing the fall of the Soviet Union as the "disintegration of historical Russia". He has claimed Russians and Ukrainians are one people, denying Ukraine its long history and seeing today's independent state merely as an "anti-Russia project". "Ukraine never had stable traditions of genuine statehood," he asserted.

It was his pressure on Ukraine's pro-Russian leader, Viktor Yanukovych, not to sign a deal with the European Union in 2013 that led to protests that ultimately ousted the Ukrainian president in February 2014.

Russia then seized Ukraine's southern region of Crimea and triggered a separatist rebellion in the east and a war that claimed 14,000 lives.

As he prepared to invade in February, he tore up an unfulfilled 2015 Minsk peace deal and accused Nato of threatening "our historic future as a nation", claiming without foundation that Nato countries wanted to bring war to Crimea. He has lately accused Nato of using Ukraine to wage a proxy war against Russia.

What's Putin's problem with Nato?

For Russia's leader the West's 30-member defensive military alliance has one aim - to split society in Russia and ultimately destroy it. In a Victory Day speech on 9 May he accused Nato of launching an active military build-up on territories adjacent to Russia.

Ahead of the war, he demanded that Nato turn the clock back to 1997 and reverse its eastward expansion, removing its forces and military infrastructure from member states that joined the alliance from 1997 and not deploying "strike weapons near Russia's borders". That means Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

In President Putin's eyes, the West promised back in 1990 that Nato would expand "not an inch to the east", but did so anyway.

That was before the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, so the promise made to then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev only referred to East Germany in the context of a reunified Germany. Mr Gorbachev said later that "the topic of Nato expansion was never discussed" at the time.

And the context in the 1990s was very different, says Barbara Zanchetta: "It was not done as a provocation, there was a partnership for peace."

Nato maintains it never intended to deploy combat troops on its eastern flank, until Russia annexed Crimea illegally in 2014.

Does Putin have designs beyond Ukraine?

If he has, his military setbacks in Ukraine may have put paid to any wider ambitions beyond its borders. The most immediate threat is to Moldova, which is not part of Nato and has already come under Russian threat.

But President Putin's ambition to roll Nato back to the late 1990s has taken a hit, with Finland and Sweden looking closely at joining an alliance that now seems as unified as ever. "He has triggered the opposite effect of what he wanted. He wanted to weaken Nato but Nato is now much stronger," says Barbara Zanchetta.

Nato has warned of a war that could last weeks, months or even years, and said its members need to be prepared for a long haul.

Russia has already punished two Nato members, Poland and Bulgaria, for the West's support for Ukraine, by cutting off their gas supplies.

Having witnessed Mr Putin's willingness to lay waste to European cities to achieve his aims, Western leaders are now under no illusion. US President Joe Biden has labelled him a war criminal and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz believes "Putin wants to build a Russian empire... he wants to fundamentally redefine the status quo within Europe in line with his own vision."

Before the war Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky paid regular visits to the front line in eastern Ukraine

War in Ukraine: More coverage

What next for Russia itself?

Russia has tried to silence dissent. Protest of any kind is banned and more than 15,000 people have been detained. "The Russian people will always be able to distinguish true patriots from scum and traitors," said President Putin.

There has been a big exodus of IT workers and other professionals and the political opposition has either fled or been jailed, as in the case of opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

A wide array of Western sanctions threaten to contract Russia's economy by up to 10% this year and hike inflation by more than 20%:

- Russia's central bank has had its assets frozen and major banks are shut out of the international SWIFT payment transfer network.

- The US has banned imports of Russian oil and gas; the EU aims to cut gas imports by two-thirds within a year and is working on a phased oil embargo; the UK aims to phase out Russian oil by the end of 2022

- Russian airlines have been barred from airspace over the EU, UK, US and Canada

- Personal sanctions have been imposed on President Putin and his entourage.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56720589