Updated on July 31, 2017, 5:10 PM GMT+8 By

Boats sit in the harbour at Brixham.

PHOTOGRAPHER: HANNAH GEORGE/BLOOMBERGThe faded Welsh industrial port of Milford Haven and the picturesque English harbor town of Brixham are economic worlds apart, but they're both desperate to leave the European Union.

Locals say Brexit can boost their fishing industry, hit by competition from foreign fleets and quotas on catches during 44 years of EU membership. The worry is that the country will repeat the mistakes on the way out they say were made on the way in by ceding to too many European demands. What they don't want is to end up with access to more fish, though fewer markets.

“There’s a lot of bargaining and we need to come down hard and do something about it,” said Mark Albery, 43, who catches lobster, crab and whelk in the waters off Milford Haven on Wales's southwestern tip. A fisherman since he was a teenager, he’s not optimistic over a favorable deal. “Not with this country, no, not at all. We just do what we’re told in the end.”

With divorce proceedings in Brussels under way, fishing exposes the paradox among some of Brexit’s most ardent supporters and the balancing act for Britain’s negotiators. People in the industry want to get back autonomy over the country and its waters to shut out foreign competition. Yet they also want to retain the benefits of the single European market with no return to borders, tariffs and bureaucracy when shipping their goods to the continent.

Brixham Trawler Agents Managing Director Barry Young holds a turbot at the fish auction in Brixham.

PHOTOGRAPHER: HANNAH GEORGE/BLOOMBERG

Despite accounting for less than half a percent of economic output, fishing is a litmus test for what Britain might be able to achieve in one of the most complicated sets of talks in modern European history.

Already, Environment Secretary Michael Gove this month announced the U.K. will unilaterally leave the 1964 London Fisheries Convention as part of its mission to “take back control” of waters up to 12 miles from its coast. At the same time, there's growing discord among ministers as to what kind of Brexit to pursue.

“All the fishermen wanted Brexit, but they’re not naïve enough to think they’re going to be able to go out there and catch all the fish they want,” said Barry Young, 46, managing director of Brixham Trawler Agents, which organizes the busy fish market in the town. “If we get something, then that’s better than nothing, which is what we have now.”

Already, Environment Secretary Michael Gove this month announced the U.K. will unilaterally leave the 1964 London Fisheries Convention as part of its mission to “take back control” of waters up to 12 miles from its coast. At the same time, there's growing discord among ministers as to what kind of Brexit to pursue.

“All the fishermen wanted Brexit, but they’re not naïve enough to think they’re going to be able to go out there and catch all the fish they want,” said Barry Young, 46, managing director of Brixham Trawler Agents, which organizes the busy fish market in the town. “If we get something, then that’s better than nothing, which is what we have now.”

The two ports, separated by 120 miles of sea and land, have different experiences since Britain joined what was the European Economic Community in 1973.

Milford Haven’s is one of rapid decline and efforts at reinvention by servicing the oil and gas industry. Brixham, meanwhile, has been thriving thanks to tourism and the cuttlefish and squid from the English Channel, with 70 percent of its produce going to other EU countries.

In the Welsh port, tiny boats bobbing in the harbor were dwarfed by huge vessels docked at Valero Energy Ltd., the petrochemical company whose thin refinery towers and steam dominate the landscape even if the smell of fish still hangs in the air. For every ton of fish brought into the port by the trawlers, almost 13,000 tons of cargo is handled for the energy industry.

Fishing vessels sit in the harbor at Milford Haven.

SOURCE: PORT OF MILFORD HAVEN

“The industry’s been decimated, absolutely decimated,” said Davies, director of Welsh Seafoods Ltd., which supplies local restaurants and hotels. “The fish has been given away. It’s not our fish anymore. It’s almost all European fish and that’s the end of it.”

In Brixham, fishermen said they managed to survive and thrive despite joining the EU and were equally resentful of the rules set in Brussels.

The town, which sits on the picturesque and palm-tree littered stretch of Devon coast that markets itself as the English Riviera, is a vibrant postcard vision of a fishing town. Candy-colored houses prettily tumble down the cliffs, overlooking the 17 million-pound ($22 million) regenerated docks.

Fish exporter Ian Perkes, right, discusses business at Brixham Market.

PHOTOGRAPHER: HANNAH GEORGE/BLOOMBERG

Ian Perkes, a fish exporter in Brixham, is eager for greater control, just not confident it will be delivered. “I don’t see it happening in my lifetime,” he said in between bidding for fish. “If we get some of the fishing rights back, fantastic. Will we? Probably not. The government will probably do a deal.”

As the clock ticks down to March 2019 and Britain’s departure from the EU, there’s still optimism fishing can be a key beneficiary.

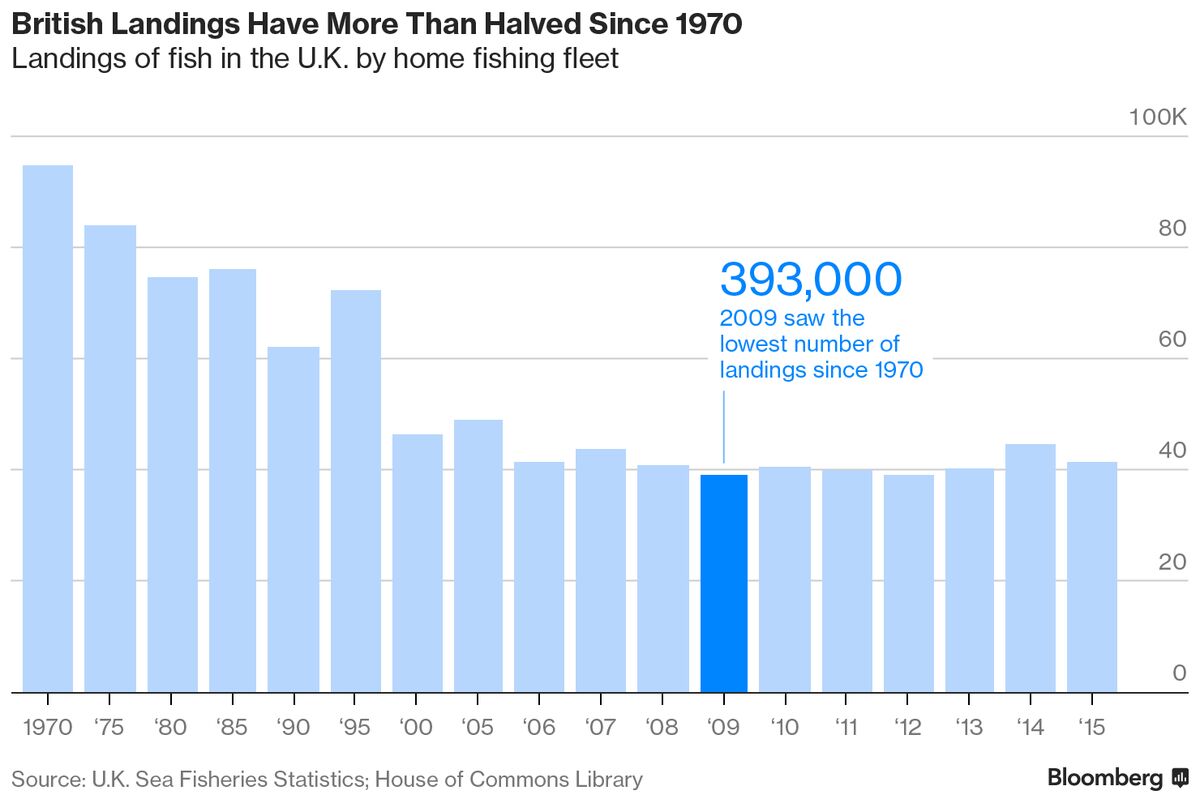

The U.K. home fleet landed 948,000 tons of fish in 1970. That number more than halved to 415,000 tons in 2015, according to government statistics. The total number of British fishermen also dropped. There were 12,000 in 2015, down from 21,400 in 1970.

Brexit is an opportunity for Milford Haven to rebuild its fleet, said Alec Don, chief executive of the town’s port authority, whose offices are perched on top of a steep cliff that drops sharply into the harbor.

“For us, the key issue is frictionless trade,” said Don, 53. “Imposing processes leading to products being delayed at borders, unnecessarily and for the sake of creating some totemic control of your borders will undoubtedly cause problems.”

The question is whether the government is able to deliver something that avoids that, said Jim Portus, head of the South Western Fish Producer Organisation.

“A lot of people said during the referendum campaign, do you really want to trust your future to ministers when it was similarly ministers that gave away our fishing opportunities in the 1970s?” said Portus, 63, as he drove around Brixham’s port area. “Are we simply going to treat our natural resources as a national asset to be traded away like the family silver?”

—With assistance from Sam Dodge and Hayley Warren

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-31/brexit-hopes-fade-for-some-who-want-it-so-badly