Fishing has always been an emotional issue in the UK's relationship with the European Union.

Supporters of Brexit see it as a symbol of sovereignty that will now be regained. The UK says any new agreement on fisheries must be based on the understanding that "British fishing grounds are first and foremost for British boats".

But the EU wants access for its boats and says reaching a "fair deal" on fisheries is a pre-condition for a free trade agreement (a deal with no tariffs or taxes on goods between the two).

So, it's hardly surprising that UK and EU trade negotiators are struggling to make headway.

How do fishing controls work?

The UK formally left the EU on 31 January, but is still bound by the EU's rules, including its Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), until the end of this year.

That means the fishing fleets of every country involved have full access to each other's waters, apart from the first 12 nautical miles out from the coast.

But they can't catch whatever they like. EU ministers gather for marathon talks every December to haggle over the volume of fish that can be caught from each species.

National quotas are then divided up using historical data going back to the 1970s, when the UK fishing industry says it got a bad deal.

That's why the government wants to increase the British quota share significantly.

It's an argument complicated by the fact that parts of the British quota have been sold off by British skippers to boats based elsewhere in the EU.

In England, for example, more than half the quota is in foreign hands.

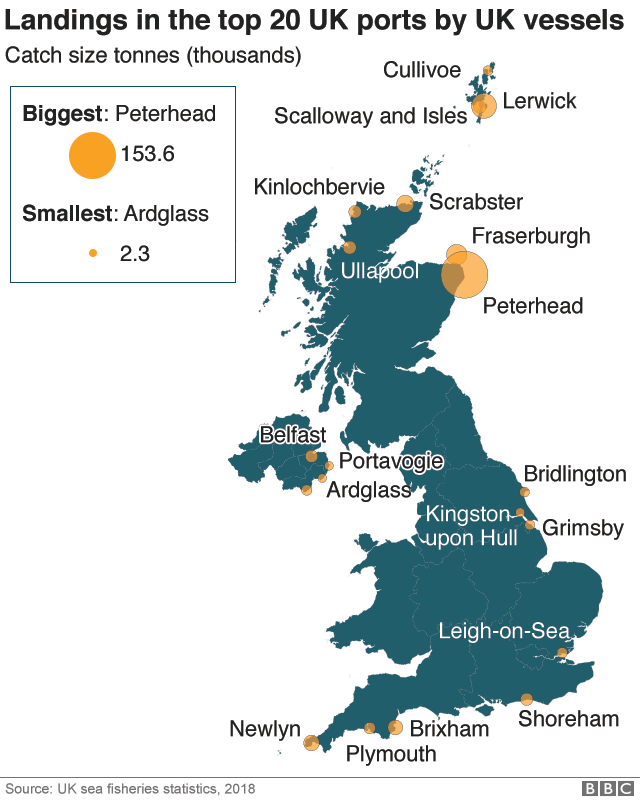

Overall, more than 60% of the tonnage landed from British waters is caught by foreign boats.

How could Brexit change this?

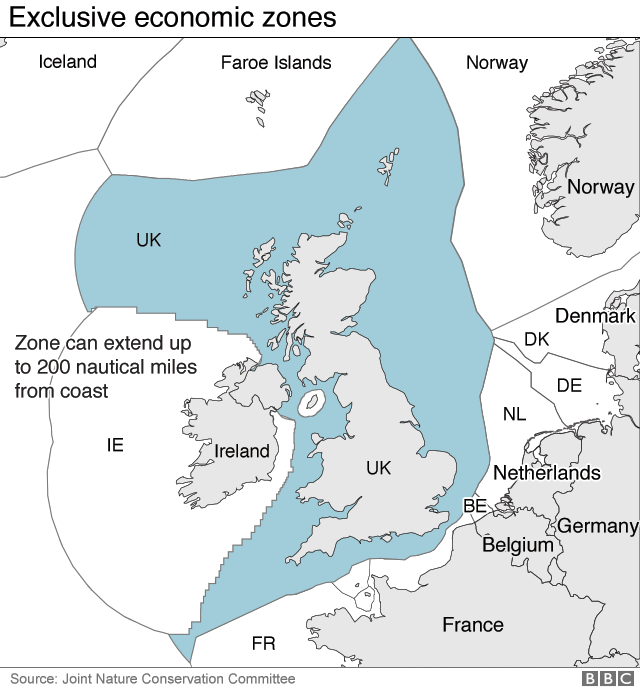

Outside the EU, as an "independent coastal state", the UK will control what's known as an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), stretching up to 200 nautical miles into the North Atlantic.

Inside the EU, the EEZs of all member countries are managed jointly as a common resource.

The government wants to hold annual talks on access to UK and EU waters, and on quotas - using a system which works out shares based on the percentage of each species of fish in each EEZ (this is known as "zonal attachment").

That's what other independent coastal states like Norway do. And fishing communities in the UK, which were strong supporters of the campaign to leave the EU, are insisting on this basic change.

But because UK waters are so important, and so bountiful, the EU is under huge pressure from its fishing communities to maintain the status quo.

It wants the UK to grant the same level of access there is now, with only gradual change envisaged, in order to "avoid economic dislocation for EU fishermen that have traditionally fished in UK waters".

The EU also wants to divide up the amounts that each country's boats are allowed to catch in a way that will not be renegotiated every year, and which cannot be changed unless both the UK and the EU agree.

The EU's chief negotiator Michel Barnier has said annual negotiations with the UK would be technically impossible because so many different types of fish would be involved.

But he has also acknowledged that the EU's current position on fishing will have to change.

"The EU wants the status quo, the UK wants to change everything," he said on 5 June. "If we want an agreement we have to discuss somewhere in between these positions."

But Mr Barnier needs to get permission from EU countries with big fishing fleets (such as France and Spain) before he seeks to compromise.

Access to markets

Either way, the UK will soon have control over who can fish in its waters.

But it's not just about where fish can be caught - it's also about where fish can be sold.

This is particularly important, because most of the fish landed by UK fishermen is exported (while most of the fish eaten in the UK is imported).

And of all those exported fish, roughly three quarters are sold within the EU. Some parts of the industry - such as shellfish - are totally dependent on such exports and would collapse if they were suddenly faced with tariffs or taxes on their products.

Proportion of UK fish exports going to the EU in 2018

That's one reason why the UK argues access to markets should be nothing to do with access to fishing waters.

But the EU is making the link explicit. Without a deal on fish, it insists, there will be no special access to the EU single market.

Complex negotiation

Plenty of other issues need to be taken into consideration, including:

- Protecting fish stocks and preventing over-fishing

- Taking account of the different priorities of big industrial trawlers and smaller boats

- Working out how fishing ranks alongside other issues in trade talks

- Nations such as Scotland wanting to go their own way

It is a complex picture.

But it's worth remembering that fishing is only a tiny fraction of the overall economy both in the UK (less than 0.1%) and in the EU (some landlocked countries have no fishing fleets at all).

According to the Office for National Statistics, fishing was worth £784m to the UK economy in 2018. By comparison, the financial services industry was worth £132bn.

Room for compromise?

In many coastal communities though, fishing is a major source of employment - responsible for thousands of jobs. The industry still has political power, and both the UK and the EU are under pressure not to give ground.

Any compromise will probably involve the UK guaranteeing a certain level of access to EU boats, which is lower (but not that much lower) than they have now.

For its part, the EU will have to agree a larger quota share for the UK and give up its demand that - in effect - nothing will change.

The two sides had initially agreed that they would try to reach a deal on fisheries by 1 July this year - a deadline that passed with almost no progress at all.

Time is now running out, soon national leaders will have to get involved, and fishing will remain one of the most difficult issues for negotiators to resolve.