Updated by Timothy B. Lee on June 25, 2016, 12:10 p.m. ET

|

On Thursday, the British people voted to leave the European Union by a 52 to 48 percent margin, a decision that has been dubbed "Brexit." It was a surprising result that will have huge consequences for Britain, the EU, and the global economy.

So why did Britain vote to leave the EU? Here are some of the most important reasons.

The euro disaster has made Brits more skeptical of the EU

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6706381/461433410.jpg) Photo Illustration by MIlos Bicanski/Getty Images

Photo Illustration by MIlos Bicanski/Getty Images

British politics has always included a faction that's skeptical of deeper integration with the rest of Europe. This faction has grown stronger in recent years as the EU has struggled with the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973 and hence the EU in the 1990s. But Britain never fully accepted the legitimacy of European control over British institutions in a way that other EU members did. It refused, for example, to join either the Schengen Area, which eliminates internal border controls, or the common currency.

Since 2008, Britain's background euroskepticism has been amplified by the poor performance of European economies.

The post-2008 recession was bad in the United States, but it was really bad in the euro area. The eurozone took a greater hit than the US did initially, and then quickly collapsed back into recession rather than experiencing a continued recovery:

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6706325/151030-US-EU-economies-GDP-growth-Knowledge-Wharton.0.jpg)

There are a number of reasons why this is true, including several EU nations' embrace of austerity. But one of the biggest, if not the biggest, cause was the euro itself.

Central banks are supposed to react to recessions by expanding the money supply in order to promote economic activity. The 2008 financial crisis caught central banks flat-footed both in the United States and Europe. But America's central bank, the Federal Reserve, ultimately responded forcefully to the economic downturn, helping to get the economy growing again starting in 2010.

In contrast, the ECB decided to raise interest rates — a contractionary policy — in 2011. The result: While the US economy started to heal, the eurozone tipped into a double-dip recession. Things got so bad, particularly in Greece, that it looked like the entire eurozone system could collapse.

This didn't affect the UK directly, as it uses the pound rather than the euro. But some Britons looked at the situation and decided that EU membership was dangerous. The EU had historically only expanded its powers, they worried. How long until Britain got roped into a euro-like disaster — or faced pressure to bail out countries whose economies were wrecked by bad eurozone economic policies?

This argument gave new potency to Britain's long-simmering euroskepticism. By mid-2012, after three years of the eurozone crisis with no real end in sight, Prime Minister David Cameron was under significant pressure from members of his own Conservative Party to hold a referendum on whether the UK should stay in. In 2013, Cameron gave a speech promising to hold just such a referendum if the Tories won Britain's 2015 election.

Advocates argued that Britain would be better outside the EU

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6706385/542730944.jpg) Photo by Mary Turner/Getty Images

Photo by Mary Turner/Getty Images

The two most common arguments in favor of Brexit focused on the EU's liberal rules for internal migration and the EU's burdensome economic regulations.

Boris Johnson, a Conservative who was then mayor of London, wrote atypical case for Brexit back in February, focusing on the increasing concentration of power in the hands of unelected EU bureaucrats in Brussels:

The more the EU does, the less room there is for national decision-making. Sometimes these EU rules sound simply ludicrous, like the rule that you can't recycle a teabag, or that children under eight cannot blow up balloons, or the limits on the power of vacuum cleaners. Sometimes they can be truly infuriating - like the time I discovered, in 2013, that there was nothing we could do to bring in better-designed cab windows for trucks, to stop cyclists being crushed. It had to be done at a European level, and the French were opposed.

On this view, the EU isn't just too meddlesome, it's also undemocratic and unaccountable to the public.

"The issue of sovereignty of who governs you, is the most important question for any country," British journalist Douglas Murray told me in an interview last week. After two decades in which significant power resided in Brussels, Murray wants to return full authority to the peoples' elected representatives in the British Parliament.

While arguments about economic regulation and political sovereignty dominate the intellectual case for Brexit, the political appeal of Brexit relies heavily on the emotionally charged issue of immigration.

Britain refused to participate in the Schengen agreement and fully dismantle border controls with other EU countries. But EU law still requires members to admit an unlimited number of migrants from other EU countries. With the eurozone suffering from dismal economic performance, a lot of workers from less affluent EU states like Poland and Portugal have moved to the UK in search of work. There's little Britain's elected officials can do to stem these flows, and that rubs a lot of British voters the wrong way.

One of the most prominent critics of the EU's immigration rules was Nigel Farage, leader of the far-right UK Independence Party. He argued that large-scale migration of low-wage workers from elsewhere in Europe has depressed wages for native-born Britons. Farage also suggested that unrestricted immigration from Europe could lead to greater competition for government services and even put British women at greater risk of sexual violence.

Farage is an extreme example — something like the Pat Buchanan of the United Kingdom. But like the US, Britain is currently experiencing an upsurge of nativist sentiments, and these attitudes are providing a boost for the campaign to leave the EU.

Support for Brexit was strongest among older and less educated voters

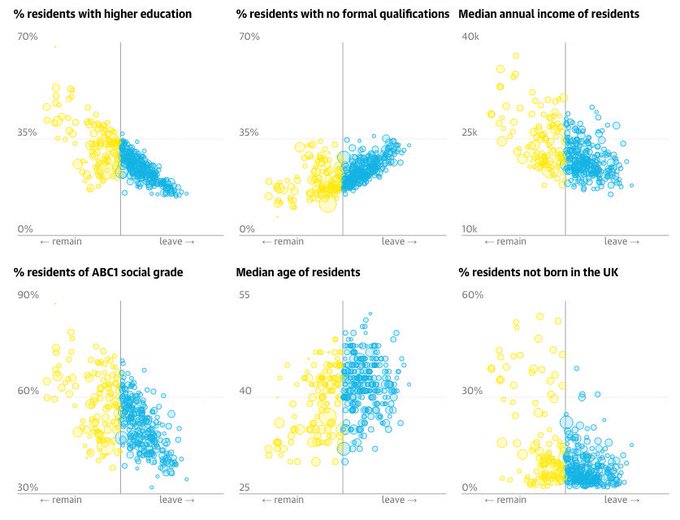

We don’t have reliable exit polls, but polls conducted the day of the referendum do give us some idea of how the vote broke down. The Brexit vote pitted young against old, urban against rural, and more educated against less educated.

According to one poll, 73 percent of voters between age 18 and 24 voted to stay in the EU, compared to just 40 percent of voters over age 65. Unfortunately for the Remain campaign, older voters turned out in greater numbers. So even though younger people were more pro-EU than older people were anti-EU, the older voters carried the day.

And as this chart from the Guardian shows, better educated voters weremore likely to vote to remain in the EU:

EU referendum results: every area by key demographicstheguardian.com/politics/ng-in…

As you can see, voting areas with more college-educated people were more likely to vote to remain in the EU. The correlation with education was even stronger than the correlation with age or income.