Three deeply intertwined stories that drove political and social change this decade, and in time may come to define European political history of the 2010’s — terrorism, Brexit, and the migrant crisis.

OLIVER JJ LANE

The most politically turbulent decade for Europe since the end of the Cold War is drawing to a close — but what will these ten years be remembered for?

It has certainly been a difficult time, if not the most difficult yet, for the European Union. The early years of the decade were dominated by the Union’s enforced policy of ultra-austerity on its southern members, particularly Greece. Suspicion at the disregard the Union appeared to treat the citizens of some nations with after Greece was later reinforced when the European Union installed its own “technocratic” government in Italy in 2011, after the government of the day hadn’t played by Brussel’s rules.

Following the collapse of the elected government of Silvio Berlusconi, Brussels made a former European Commissioner the Italian Prime Minister, creating the first of three EU-backed technocratic Italian governments. These moves and others continue to linger in the minds of Eurosceptics across the continent years later.

Yet perhaps even greater developments may colour memories of the decade — the deadly terror attacks striking against European cities and peoples, the decision of one European politician to unilaterally declare the continent open to mass migration, and the all-consuming debate on Britain’s withdrawal that hasn’t even happened yet.

As we enter a new decade, events that define the last:

The Migrant Crisis

RIGONCE, SLOVENIA – OCTOBER 23: Migrants are escorted through fields by police as they are walked from the village of Rigonce to Brezice refugee camp on October 23, 2015 in Rigonce,, Slovenia. (Photo by Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

Future historians may well remember the 2010’s — ironically — as the “Wir schaffen das” or ‘we can do it’ decade. This phrase, uttered by Germany’s Angela Merkel in 2015 was in response to criticism that already prodigiously generous Germany not doing enough to help migrants.

That, and the expressions of Germany’s so-called Welcome-culture were interpreted as an open invitation by many — so many, in fact, that over a million illegal migrants and ‘refugees’ are known to have crossed into Europe in just one year, with over 800,000 of them crossing into the continent by sea.

Germany opened her borders to all comers in 2015, de facto throwing the borders of Europe open unilaterally, and in doing so triggered the Europe Migrant Crisis. The summer’s news was of the enormous suffering caused by Angela Merkel’s carelessness — the thousands killed on unseaworthy boats sent by ruthless human-traffickers making the most of her largess to make quick money — and of great columns of people marching north.

While in a sane world the migrant crisis shouldn’t have been possible, a combination of factors including the European Union’s much-vaunted but now discredited open borders scheme and Germany suspending the EU laws which were designed to prevent migrants crossing the continent looking for the most generous country rather than the first safe one, meant it was.

At times, the through-flow of migrants heading north through the Balkan route and central Europe was so great the number of illegals being waved through national borders was tens of thousands every single day.

While some countries opened their borders, others resisted being co-opted into Germany’s mass migration scheme. Hungary, one of the last stops on the way north and a key road and rail hub for illegals heading to Germany saw up to 10,000 migrants a day in mid-2015, but the completion of their southern border fence in October of that year saw daily arrivals suddenly fall to pre-crisis levels, more or less overnight.

Registered, known illegal immigration to Hungary fell from 391,000 in 2015 to just 1,184 in 2017.

As the left in Europe mourns the end of a decade which saw the collapse of their political movements and the rise of the populist right across Europe, it is worth noting far-sighted left-politicians foresaw what damage to their own credibility the migrant crisis would do. European Commission vice president Frans Timmermans — who is still in post and these days delights in meddling with the Brexit process — warned in 2015 that unless the establishment could find “sustainable solutions” to the migrant crisis, there would be a surge of right-wing populism across Europe.

Terrorism

TOPSHOT – Authorites inspect a truck that had sped into a Christmas market in Berlin, on December 19, 2016, killing at least nine people and injuring dozens more.

Ambulances and heavily armed officers rushed to the area after the driver drove up the pavement of the market in a square popular with tourists, in scenes reminiscent of the deadly truck attack in the French city of Nice last July. / AFP / Odd ANDERSEN (Photo credit should read ODD ANDERSEN/AFP via Getty Images)

Ambulances and heavily armed officers rushed to the area after the driver drove up the pavement of the market in a square popular with tourists, in scenes reminiscent of the deadly truck attack in the French city of Nice last July. / AFP / Odd ANDERSEN (Photo credit should read ODD ANDERSEN/AFP via Getty Images)

The 2010s for Europe was a decade pock-marked by the horror of radical Islamist terror, with a large number of high-profile, high-casualty attacks visited upon its cities and people, and dozens more intercepted by the security services before they could come to fruition.

Indeed, the decade began with an attempted attack — fortunately for its intended target, failed– on January 1st 2010, when a Somali migrant armed with an axe tried to kill Danish artist Kurt Westergaard in his home. The motivation for the attack is one now all too familiar in Europe — Mr Westergaard had drawn a cartoon of the Islamic prophet Mohammed.

Later, nearly the entire editorial magazine of a French satirical magazine were gunned down in their own offices during a weekly meeting. Again, their crime had been to be undiscriminating in their lampooning, having made as much fun of Mohamed as of any other prophet or god. The vast majority of European mainstream media outlets chose to be cowed by the attacks rather than stand in solidarity with the dead, refusing to publish the images the men and women of Charlie Hebdo had been murdered for.

More attacks followed, and at an accelerating pace as the decade wore on. 2013 introduced Europe to a new kind of terror when a pair of Islamist converts rammed their car into a soldier on a London street and attempted to decapitate him with kitchen knives. While the name of Drummer Lee Rigby lives on, the car-knife attack became the weapon of choice for Islamist killers this decade and is now better known to ordinary people across Europe. Requiring no complex planning or acquiring illegal weapons or explosives, the method was promoted by the Islamic State themselves as ideal for killing the unbelievers.

While many terror attacks against Europe were perpetrated by so-called “homegrown” radicals — arguably a product of the doctrine of multiculturalism encouraging balkanised communities going their own way, rather than pulling together and integrating into national cultures — this has not always been the case. The gunman at the 2014 Jewish Museum attack had fought in the Syrian civil war before coming to Europe, and some of the attackers in the 2015 Bataclan massacre — in which 131 were killed with Yugoslavian AK47-clones and explosives — had also fought in Syria, thought to have entered Europe while posing as refugees during the migrant crisis.

Taking the automobile method to its logical conclusion, 2016 saw two truck attacks, using the largest and deadliest vehicles on the road to kill the largest number of Europeans. In the French city of Nice on their national day, a Tunisian migrant drove a rented 19-ton truck into crowds enjoying a seafront promenade party. Driving at over 50 miles an hour, 86 were killed.

This was followed up months later when a failed asylum seeker — who too had come to Europe on a migrant boat — murdered the Polish driver of a semi-truck and used the hijacked vehicle to drive through the Berlin Christmas market, killing 11.

The late part of the decade also saw a string of attacks in the United Kingdom. There was a vehicle-knife attack in Westminster in March 2017 which culminated in a police officer being stabbed to death inside the British Parliament’s own walls, and the Manchester arena bombing which targeted children and their parents as they left an Ariana Grande concert which killed 22 and injured over 800.

Then London was revisited with another vehicle-knife attack at London Bridge later that year, where eight died. The scene would be targeted a second time in 2019 with yet another attack as a recently released extremist went on a knife rampage before being subdued by members of the public armed with improvised weapons.

The routine responses to these attacks has, too, become part of the grim background of European urban life in the 2010s — the inevitable ‘Love [insert city name]’ posters, teddy bears and tealights. Anti-terrorism barriers and police officers dressed like military special forces are now an apparently permanent feature of our streets. But as London mayor Sadiq Khan likes to point out, it’s all part and parcel of living in a big city.

Brexit

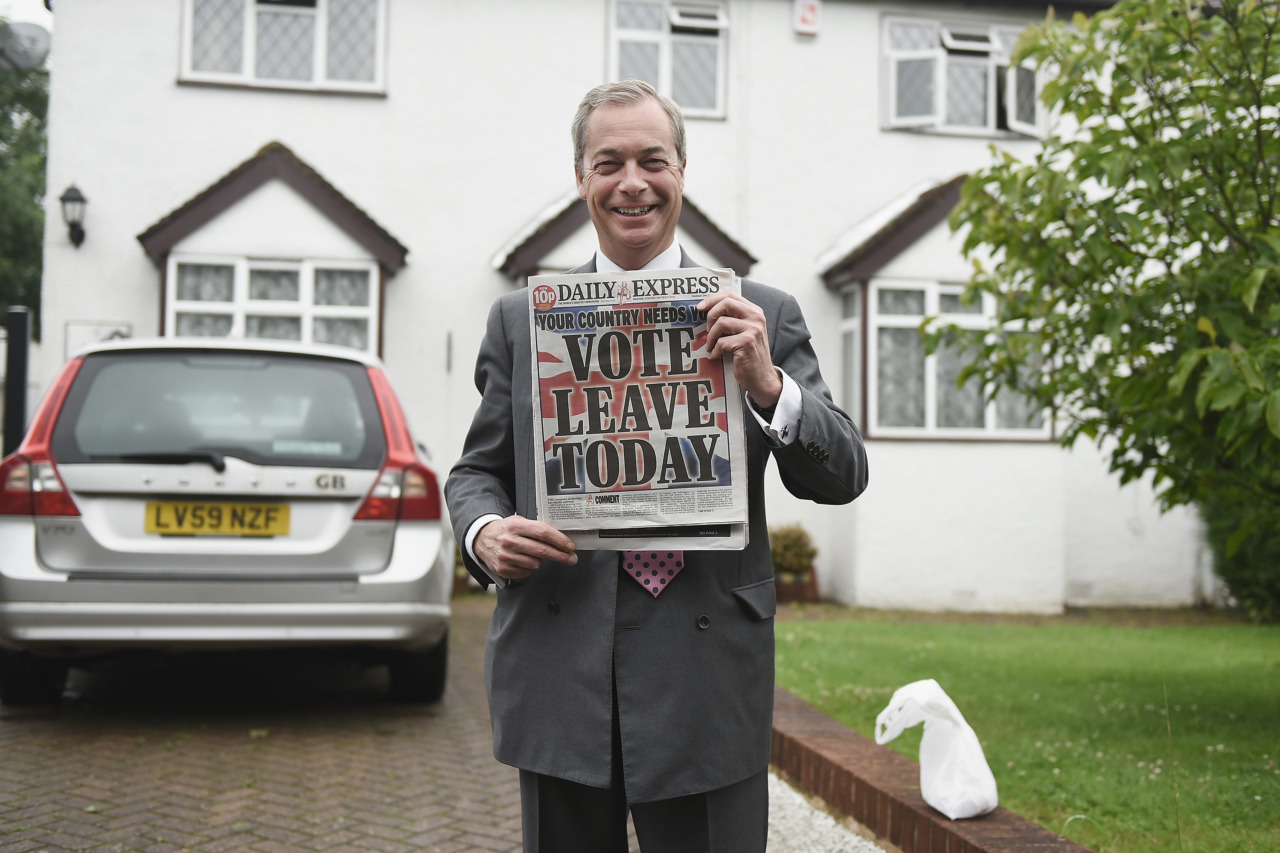

WESTERHAM, ENGLAND – JUNE 23: Nigel Farage, leader of UKIP and Vote Leave campaigner holds up the ‘Daily Express’ as he returns to his home after buying newspapers of the United Kingdom on June 23, 2016 in Westerham, England. The United Kingdom is going to the polls to decide whether or not the country wishes to remain within the European Union. (Photo by Mary Turner/Getty Images)

If the 2010s were the Brexit decade, then Nigel Farage must have been the man of the decade. What other individual can claim to have had such a profound and widely felt impact on the whole continent in the past ten years — quite apart from how it has utterly dominated British politics, Brexit has near totally paralysed the European Union itself.

Every major European summit for years has been consumed by Brexit discussion, repeated Brexit deadlines and the false sense of urgency that always accompanies the down-to-the-wire negotiations Brussels runs on have run roughshod over every other concern. Most frustrated by this has clearly been France’s Emmanuel Macron, who clearly saw his domestic rise to power as an insignificant stepping stone on his mission to totally reform Europe.

Hence his being by far the keenest European leader to get Britain out of Europe as soon as possible — if his poll ratings are anything to go by his time as French president are numbered and with that his chance to make his mark on history. This is all great news for the actual people of Europe, of course, who might take the view the less Eurocrats in Brussels are capable of actually doing the happier and easier their day to day lives can be.

Brexit itself had been on the slow-boil for decades, the nascent Eurosceptic movement — having all but vanished in 1973 after the county voted to stay in the European community on the basis of a pack of half-truths from then Prime-Minister Ted Heath who withheld the truth he knew about the future direction of Europe — getting a kick-start with the Maastricht treaty in 1992. Signing the European Union into existence, the push by the British government to support the move and take the country into ever-closer union with Europe all but split the Conservative party.

Nigel Farage — then an unknown — was one of many to leave the Conservatives at the time over their direction on Europe. A founding member of the UK Independence Party in 1993, Mr Farage has been a persistent character of this decade, having come to national attention after suffering a broken sternum, broken ribs, and punctured lung in an air-crash on the morning of the 2010 general election.

While all will remember the 2016 referendum, 2014 was the year Britain’s fortunes turned with respect to the European Union. In the European Union parliament elections of that year, UKIP became the first party other than Labour or the Conservatives to win a national election in over a century, setting alarm bells ringing among the establishment parties in Westminster.

Desperate to not have his leadership torn apart by the European issue as it has John Major’s in 1992, then Prime Minister David Cameron promised an in-out referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union as a means to appease Eurosceptics in the 2015 general election. This was an easy promise for Mr Cameron to make — neither he nor the pollsters expected him to win the vote outright, and another coalition government would give him ample opportunity to renege on the pledge.

Yet he romped home with 24 more seats, so Mr Cameron gave Britain the referendum he’d promised. Again an easy decision for him — the Prime Minister, all his colleagues, the people they socialised with, other world leaders, and the pollsters all believed he’d easily win the vote, and in doing so would put the issue of Europe to bed for another generation. To make the gamble a sure one, the government threw its full weight behind the remain side, wrote to every household in the country explaining why the European Union is a good thing, and indulged in what was then called project fear.

Well, we know how that went. Yet almost four years later the United Kingdom still hasn’t left the European Union but seems all but certain to do so and new Prime Minister Boris Johnson is promising a decade of growth, prosperity… and Brexit.

https://www.breitbart.com/europe/2020/01/01/terrorism-brexit-and-the-migrant-crisis-three-stories-that-defined-the-decade/